![]()

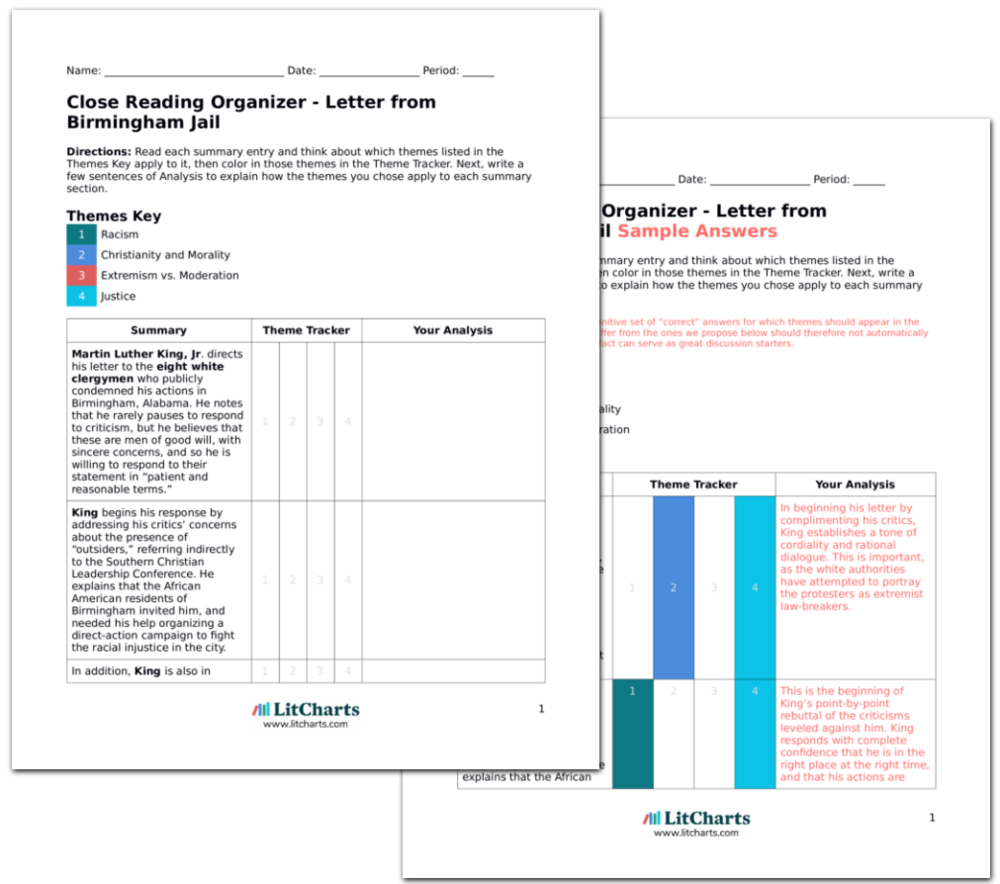

LitCharts assigns a color and icon to each theme in Letter from Birmingham Jail, which you can use to track the themes throughout the work.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Martin Luther King, Jr . directs his letter to the eight white clergymen who publicly condemned his actions in Birmingham, Alabama. He notes that he rarely pauses to respond to criticism, but he believes that these are men of good will, with sincere concerns, and so he is willing to respond to their statement in “patient and reasonable terms.”

In beginning his letter by complimenting his critics, King establishes a tone of cordiality and rational dialogue. This is important, as the white authorities have attempted to portray the protesters as extremist law-breakers.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King begins his response by addressing his critics’ concerns about the presence of “outsiders,” referring indirectly to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference . He explains that the African American residents of Birmingham invited him, and needed his help organizing a direct-action campaign to fight the racial injustice in the city.

This is the beginning of King’s point-by-point rebuttal of the criticisms leveled against him. King responds with complete confidence that he is in the right place at the right time, and that his actions are necessary.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

In addition, King is also in Birmingham because he feels compelled to respond to injustice wherever he finds it. He compares his work to that of the early Christians, especially the Apostle Paul , who traveled beyond his homeland to spread the Christian gospel. Finally, he questions the idea that anyone in the United States can be considered an outsider within the country, and that the injustice affecting those in Birmingham is inherently connected to racial injustice on a national scale.

As a Baptist minister, King has a depth of knowledge of the Bible and history of Christianity, which he uses to his advantage in this letter. He knows that comparing the protesters to the early Christians places his critics in the role of the enemies of freedom. He then reminds his critics that the protesters are American citizens, and therefore they are not outsiders in their own country.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

According to King , the systemic racism in Birmingham has left the African American community with no alternative to direct action. He points to the city’s segregation, police brutality toward the African American community, their mistreatment in the courts, and the unsolved bombings of African American homes and churches as examples of the conditions that make nonviolent protest necessary at this point in history.

While his critics have expressed concern about his behavior, King turns the tables on them and focuses on the systemic racism that white authorities have ignored for far too long. King emphasizes that the protests are a necessary action based on African Americans’ current social and political conditions.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

"My students can't get enough of your charts and their results have gone through the roof." -Graham S.

In the past, the African American community has attempted to negotiate with Birmingham community leaders, but had their hopes dashed. King cites the local merchants’ promise to remove their “humiliating racial signs” that established and supported segregation in downtown stores, in exchange for a moratorium on political demonstrations. Only a few merchants actually took down their signs, and even then, some put them back up after a while. This convinced the African American community that they needed to take direct action through civil disobedience.

King goes into detail about the steps that have gone into this decision to protest, and again focuses on the failings of the white authorities. By describing the signs as humiliating, King calls attention to the psychological effects of segregation for African Americans. The merchants’ disingenuous dealings with African American leaders only exacerbates that humiliation.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King clarifies that the goal of the protests was to force the situation, and “to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.” He has found that overall, people will not give up their privileges without intense pressure to do so, and so they must apply that pressure through protest.

King asserts that the goal of the protests is to create an atmosphere of discomfort for whites in Birmingham. His critics’ vehement condemnation of the protests, then, is a sign that they are, indeed, creating the pressure needed to spark change.

Active Themes![]()

Some of his critics have described the protests as untimely, and suggested that the protesters wait for desegregation to happen on its own schedule. King replies that they have waited 340 years for their “constitutional and God-given rights,” and that for him, the word “wait” is equal to “never” in the context of civil rights.

The question of time comes up often in the struggle for civil rights, and King dedicates a large portion of his letter to responding to this issue from the African American perspective.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

To give his readers an idea of the racial injustice African Americans have experienced, King offers a list of injustices. He presents examples of lynchings and extreme police brutality, the “air-tight cage of poverty,” and the emotional pain of explaining segregation to his young daughter, only to see “ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky.” He delves into the psychological effects of being a second-class citizen in his own country and concludes that he can no longer wait for change to happen on its own and must go out and make it happen.

In this section of the letter, King humanizes African Americans by focusing on the emotional and psychological pain that segregation and racial inequality have caused. His anecdote about his daughter presents the human side of a heavily politicized issue. Alongside the more obvious threats of death, bodily harm, or imprisonment, African Americans suffer from more complex issues like financial uncertainty and a sense of inferiority.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King moves on to discuss the fact that he and the other protesters are breaking laws, which the eight white clergymen mentioned among their many criticisms. He specifies, however, that the laws they are breaking are unjust, and that he feels a moral obligation not to follow unjust laws.

Returning to the specific list of criticisms, King now focuses on distinction between law and justice. He does not deny that his protests are illegal, but instead calls into question the validity of the laws he has broken.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King establishes the grounds for deeming a law unjust, focusing specifically on whether or not the law—a man-made concept—corresponds to moral or natural laws, which are established by God. In this way, he deems segregation unjust because it is “an existential expression of man’s tragic separation, his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness.” More concretely, he notes that a law is unjust if those made to obey the law (in this case, African Americans) had no opportunity to enact that law.

King presents a solid legal argument in this section, while still focusing on morality in a Christian context. Again, because he is attempting to engage in dialogue with his fellow clergymen, King reminds his readers that religious moral codes should have a higher status than the laws of the land. In this way, King establishes that segregation is an immoral—and therefore unjust—law.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

Most importantly, King notes that he and his fellow protesters are willing to accept the punishment for breaking the law, and therefore they are showing the highest respect for the institution of law itself. He reminds his readers of the history of civil disobedience, which harkens back to the early Christians that resisted the unjust laws of Nebuchadnezzar and the Roman Empire, all the way to the Boston Tea Party , one of the foundational acts of civil disobedience in American history.

King establishes the difference between ordinary crime and civil disobedience. At the center of civil disobedience is the public nature of law-breaking: these African Americans are protesting publicly, and allowing themselves to be arrested, to bring attention to the unjust laws. King again compares the protesters to the early Christians, creating a moral and ethical connection between the two groups.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King then offers his own criticisms, condemning the white moderate for his passive acceptance of racial inequality, calling him more dangerous than the Ku Klux Klan . The white moderate is dedicated to order over justice, while King and his fellow protesters must disrupt that order to expose injustice.

One of King’s central points in this letter is that moderation is not a politically prudent tactic, especially when African Americans find themselves in the kind of physical, emotional, and psychological danger that he described earlier.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

To illustrate the white moderate perspective, King refers to a letter he received from a white man from Texas, who claimed that King was “in too much of a religious hurry” because equal rights would come on their own schedule. King contends that it is not just time what will bring about civil rights, but the “tireless efforts of men willing to be coworkers with God.” The idea that time—without the support of human action—will bring about change is a tragic misconception of time itself.

King describes the white moderate as complacent, hypocritical, and condescending toward African Americans, agreeing on the surface with their overall goals (freedom, political participation, and equality) but unwilling to take any steps to fulfill them. King thus emphasizes the role of action (in the form of nonviolent protest) as the only way of making change.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

King then addresses the description of the protests as extreme, arguing that he and the SCLC fall somewhere in the middle, between African Americans who have become complacent and have no desire to fight for their freedom, and the black nationalist groups that are consumed by bitterness and hatred of whites. Their movement is a third way of nonviolent protest.

The next critical point King addresses is the question of extremism, which his critics have used as an insult or warning, and by which they hope to de-legitimize the civil rights movement. King uses the example of the black nationalist parties as real extremists, especially due to their lack of Christian values.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

The yearning for freedom is the result of centuries of pent-up frustration, and if African Americans do not have the opportunity to take action and participate in nonviolent protest, King argues, they will find refuge in the more extreme groups. He asks his critics to consider the circumstances that brought about these protests, rather than automatically condemning them.

King continues to request that his critics consider the issue from the point of view of the protesters, and this time he emphasizes the fact that there are other, much more extreme options for frustrated African Americans.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

King then changes his mind about the term extremist, embracing the idea within the context of Christianity and American history. He notes that Jesus was an extremist for love, Paul for the Christian gospel, and Martin Luther for Reformation. Likewise, Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson were extremists for their causes, which eventually became fundamental values in American politics.

King redefines and embraces the term “extremist.” Like the other extremists he lists, King believes that his cause will win out in the long run, and that he is on the right side of history. He also includes examples from American history, thus placing his critics in the place of historical villains, such as the British.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King returns to his condemnation of white moderates, lamenting the fact that they have not been able to see this fundamental need for civil rights. He points out, however, that there have been some exceptional allies, who have used their words and bodies to show their commitment to racial equality. He also commends one of the eight white clergymen specifically: Reverend Stallings welcomed African Americans to worship alongside whites, integrating his church service.

Throughout the letter, King has maintained a cordial and generous tone, careful to show respect for his critics even when they do not merit it. He now commends some of the white people who have supported the cause of racial equality in even the smallest ways, such as the Reverend Stallings.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

With these notable exceptions, King comments, he is disappointed with the white church. He believed that as Christians, they would understand and support the cause and preach the gospel of racial equality as he does. What he has found is too much caution, and a desire to separate the church from the needs of the community.

King’s commendation of these allies is strategic, however, as he then condemns the majority of the white church leaders who have not made the same small concessions that Reverend Stallings did. King returns to his criticism of white moderates and their unwillingness to take action.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

He reminds his readers of the time when the Christian church was powerful and functioned as an agent of change; he no longer sees that in the contemporary church, which he calls “an archdefender of the status quo.” If this continues, warns King , the church will lose the loyalty of millions and lose its relevance in the lives of young people.

King believes that one of the most important roles of the Christian church is to help drive transformation, and in this way, he links his objective of racial equality with their desire to stay relevant to modern Americans.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King again praises those who have taken the risk and joined the cause of racial equality, expressing hope that the rest of the church will follow their lead. Yet even without the support of white religious leaders, King believes that the protesters will eventually triumph. He announces that they will achieve the goal of racial freedom “because the goal of America is freedom.”

King moves on to tie the current struggle for racial freedom to the historical struggle for American independence from Britain. These connections help to build community with his critics: the protesters are also Americans and members of the church, and should not be viewed as enemies.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

In a final point before closing his letter, King notes that white leaders have commended the police for their work maintaining order and preventing violence. He takes issue with this commendation for two reasons: first of all, King argues that these white leaders have not seen the violent treatment of African Americans that hardly merits commendation, like physically abusing men, women, and children, and refusing them food in the city jail.

This final point in the letter returns to the present moment, where the police can abuse African Americans and still receive a commendation from leaders of the religious community. When these leaders praise the police for preventing violence, they are only concerned about violence against white citizens.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

Yet even when the police have conducted themselves nonviolently in public, King argues that this is not worthy of praise, either. Regardless of their conduct, the police are working to preserve the racist and violent laws of segregation, and King does not see that as worthy of praise.

Focusing on the larger picture, King reminds his critics that the segregation laws are unjust, as he has shown, and thus that there is no justice in upholding unjust laws. The preservation of order is not as important as the fight for justice.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King expresses his wish that these same leaders had commended the protesters in Birmingham for their courage and discipline in the face of injustice. He argues that one day, these people will be the real heroes, commended for their suffering and persistence in the fight for racial justice and for supporting the democratic process that is the cornerstone of American history.

King takes the opportunity to praise the protesters, in part because no white religious leader will do so. In his praise, King shows his confidence in the righteousness of his cause and his belief that while he may not see the end of segregation, he knows history will be on his side.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

King finishes his letter with a few final notes. First, he apologizes for the length of his letter, but reminds his readers that he is sitting in a jail cell, with nothing else to do but ruminate on the conditions that have brought him there. He then expresses a desire to meet with the eight white clergymen who have criticized the protests—not as an African American or a protester, however, but as a fellow clergyman. He completes his letter “yours in the cause of Peace and Brotherhood.”

Signing off, King re-positions himself for his critics one final time: he is like them, a religious leader looking to spread the gospel of peace and community. Yet unlike them, he has been jailed for his actions. He uses the fact that he is writing from a jail cell to remind his readers of the injustice and absurdity of the situation.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

“Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!”

Get the Teacher Edition

“This is absolutely THE best teacher resource I have ever purchased. My students love how organized the handouts are and enjoy tracking the themes as a class.”

Copyright © 2024 All Rights Reserved Save time. Stress less.AI Tools for on-demand study help and teaching prep.

Quote explanations, with page numbers, for over 44,324 quotes.

Quote explanations, with page numbers, for over 44,324 quotes. PDF downloads of all 2,003 LitCharts guides.

PDF downloads of all 2,003 LitCharts guides. Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level. Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level. Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.